Taking the high road towards sustainable mobility

Human-centric design is falling short when it comes to paving the way towards sustainable mobility. It’s time to think bigger and ensure the future of mobility serves both people and the planet.

This article is part of Finding the way forward, our publication focusing on new mobility in the age of data, platforms and ecosystems. Download the publication here, and learn more about our approach to the mobility industry here.

The past few years have seen a rapidly growing degree of awareness on sustainability, and more importantly, increasing adoption of sustainable practices in businesses across industries. This is particularly important for work against climate change, which depends on collaborative effort on a global scale.

Make no mistake, organisations in the mobility business are at the very centre of this transformation. Roughly a quarter of global CO2 emissions come from the transportation of people and goods, which is a fairly clear indication that prompt action is needed.

This, of course, applies to developing new services and offerings as well as adapting existing ones to better tackle the challenges at hand. This article will discuss different ways for the mobility industry to approach sustainability challenges.

The future of mobility requires a shift from individual to collective optimisation

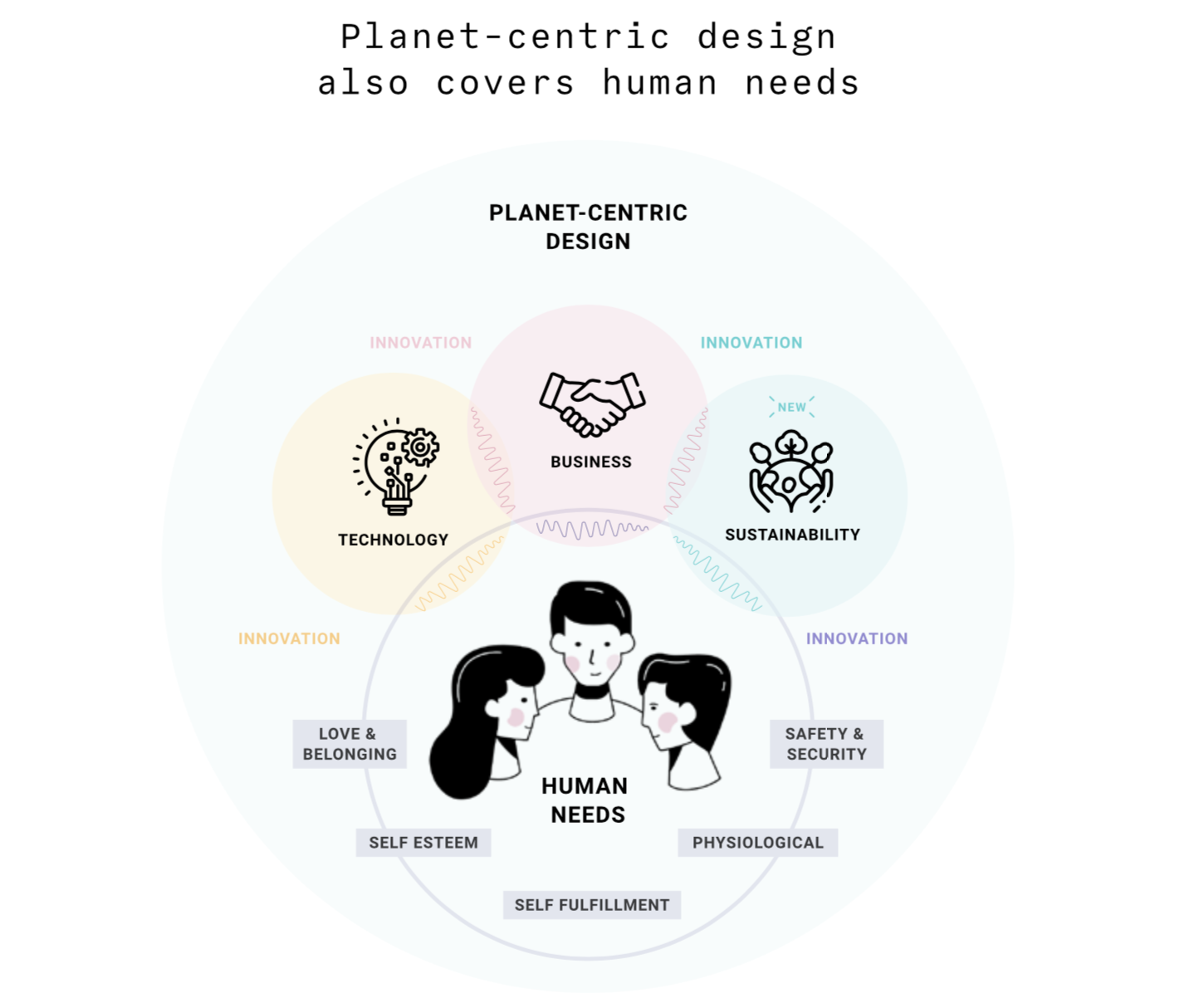

For the past few decades, human-centric design has been a key element of design and innovation studies as well as a prominent principle in real-world use. Building on Maslow, human-centric design is largely based on the fulfillment of basic human needs such as physiology, safety, social and individual needs as well as self-actualisation.

This mode of thinking, however, comes with a major issue: short-term thinking and emphasis on individual needs at the cost of the big picture and society – things like the environment, overall traffic flow, or safety – does not contribute to a sustainable world for the collective. As we’ve already learned in several large cities, e-scooters are admittedly very convenient, but they are also problematic particularly for the elderly and people with disabilities when haphazardly parked. We believe it’s possible to change the direction of this development, but we need to adapt our thinking, tools and models.

What is the next step after human-centric design?

People have the tendency to favour comfort, and often choose the path of least resistance. Preferences don’t change overnight, but we can help change behaviours by incorporating the UN’s sustainable development goals into product and service development to create services that are better for the planet and people.

To make this happen, it’s time to evolve human-centric design thinking into something larger and more sustainable, and embrace planet-centric design instead.

This shift involves not just updating methods, but also including sustainability into criteria for deciding between different options and courses of action. We need to start asking ourselves what impact our opportunities have on the environment and society, and only move forward with business cases with a positive sum total. Our Lean Service Creation methodology, for example, approaches this with a canvas dedicated to sustainable design that helps teams assess the overall impact of their products and services also beyond the individual user.

The idea of planet-centric design is to take the foundation of human-centric design and build on top of it towards common good, rather than abandon the previous paradigm altogether. Planet-centric design isn’t concerned solely with the environment, but also covers social issues, economic stability and sustainability on a strategic level.

Properly addressing these issues can offer significant competitive advantages and help secure new business as well as solidify relations with existing customers. Post hoc greenwashing efforts, unsurprisingly, lack this effect.

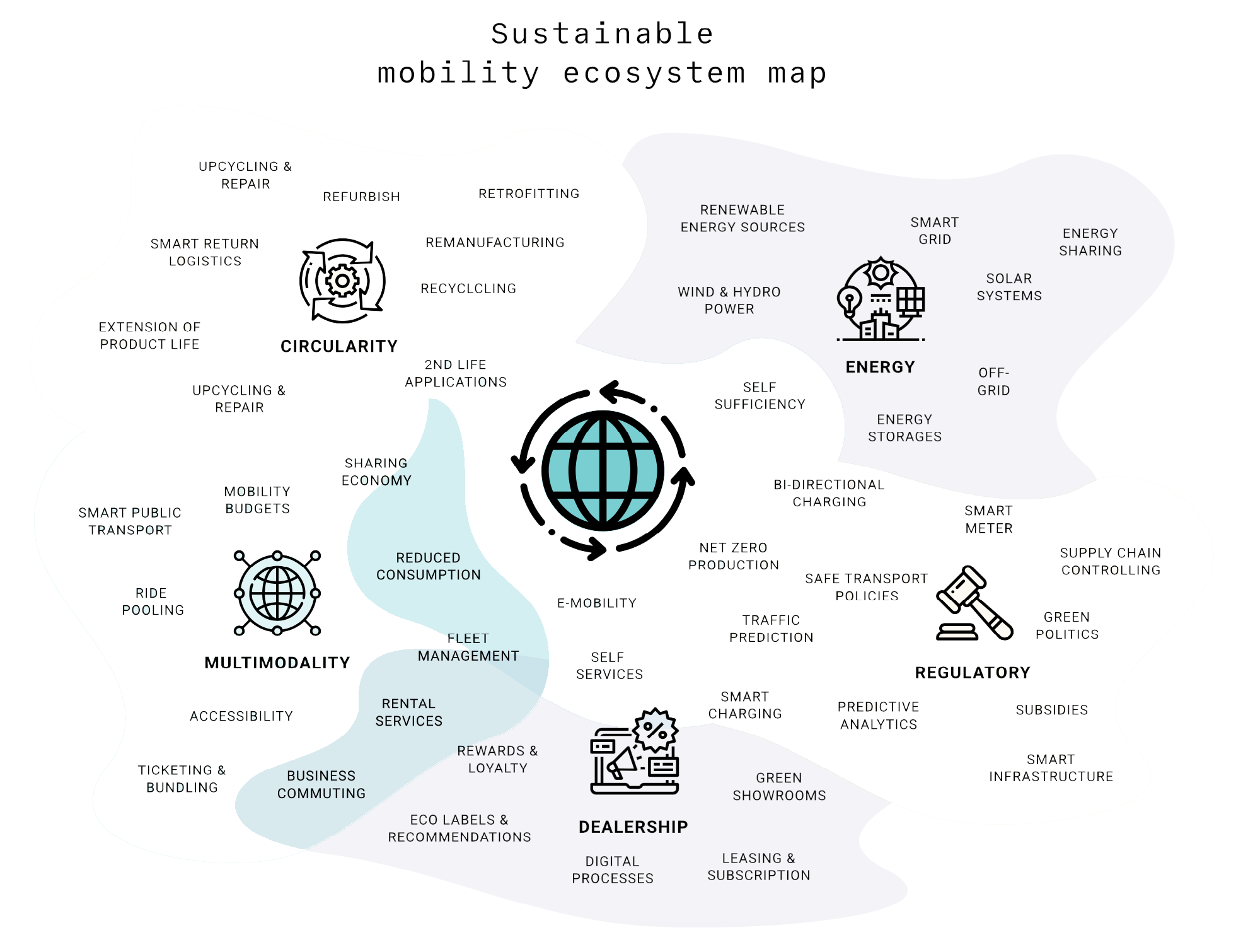

What does sustainability mean for the mobility ecosystem?

There are many ways to approach sustainability. Startup businesses have the ability to adopt and encode sustainable ways of working directly into their DNA, while on the other hand, incumbent companies enjoy the luxury of utilising their existing assets and product portfolios to make a big difference.

When it comes to sustainability, there are no one-size-fits-all solutions due to the enormous complexity between – and even within – different industries and domain areas. When initiating the development of new products or services, it is necessary to agree on relevant (and sufficiently ambitious) sustainability criteria for the context at an early stage, and ensure common understanding through concrete examples.

This naturally places a lot of responsibility on product and service designers. Evaluating and selecting valid criteria for sustainability should involve careful 360° research: reviewing studies from relevant academic and business domains, forming hypotheses, and validating them with experts – ones who aren’t only familiar with the mobility sector, but also have a deep understanding of sustainability. After that, on a more practical level, assessing sustainability should involve systematic experimentation and testing hypotheses under real-world conditions.

How technology can support sustainability in mobility

In short, sustainable mobility is about creating increasingly sustainable business models by strengthening the offering of different modes of mobility and boosting them with new technologies and the smart use of data. The decisive factor will be how we’ll succeed in using different modes of transport in a sensible manner to reduce individual traffic and habitual journeys.

What makes the most sense varies greatly from situation to situation. The overall offering is expanding gradually through intermodality, and ideally, the goal should be to create more opportunities of everyday mobility.

Thanks to integrations and a wealth of data, external factors such as weather, distribution of vehicles, local demand, traffic jams, construction sites, and CO2 emissions can be taken into account in real time. Slower vehicles such as e-scooters and cargo bikes can further increase flexibility by complementing the traditional offering, and in new residential areas, shared fleets can help plan flexible mobility concepts.

But the abundance of data also has a flipside: it adds more complexity, making it more difficult for people to make informed decisions on their own. This, in turn, lowers the barrier for consumers to choose the cheapest option at the expense of the environment. Fortunately, making sense of messy situations is a prime use case for artificial intelligence (AI). Implementing AI to quickly calculate different variables, identify problems and analyse scenarios will be instrumental in helping the masses make better decisions.

Additionally, rapidly growing cities mean increasing numbers of people on the move. This translates into more traffic in metropolitan areas, and introduces new challenges in terms of safety, reliability, and maintenance. The situation calls for more attention to the division of space and physical traffic arrangements as well as new investments into smarter, data-enabled traffic control measures.

Real-time traffic analysis enables the optimisation of traffic flows on the basis of data. Combining location-based insights with cell tower data can help avoid traffic jams and save time, and by extension, also lower the risk of accidents. Identifying congested areas as well as the time and duration of traffic disruptions can be massively beneficial in predicting and relieving problems before they actually manifest.

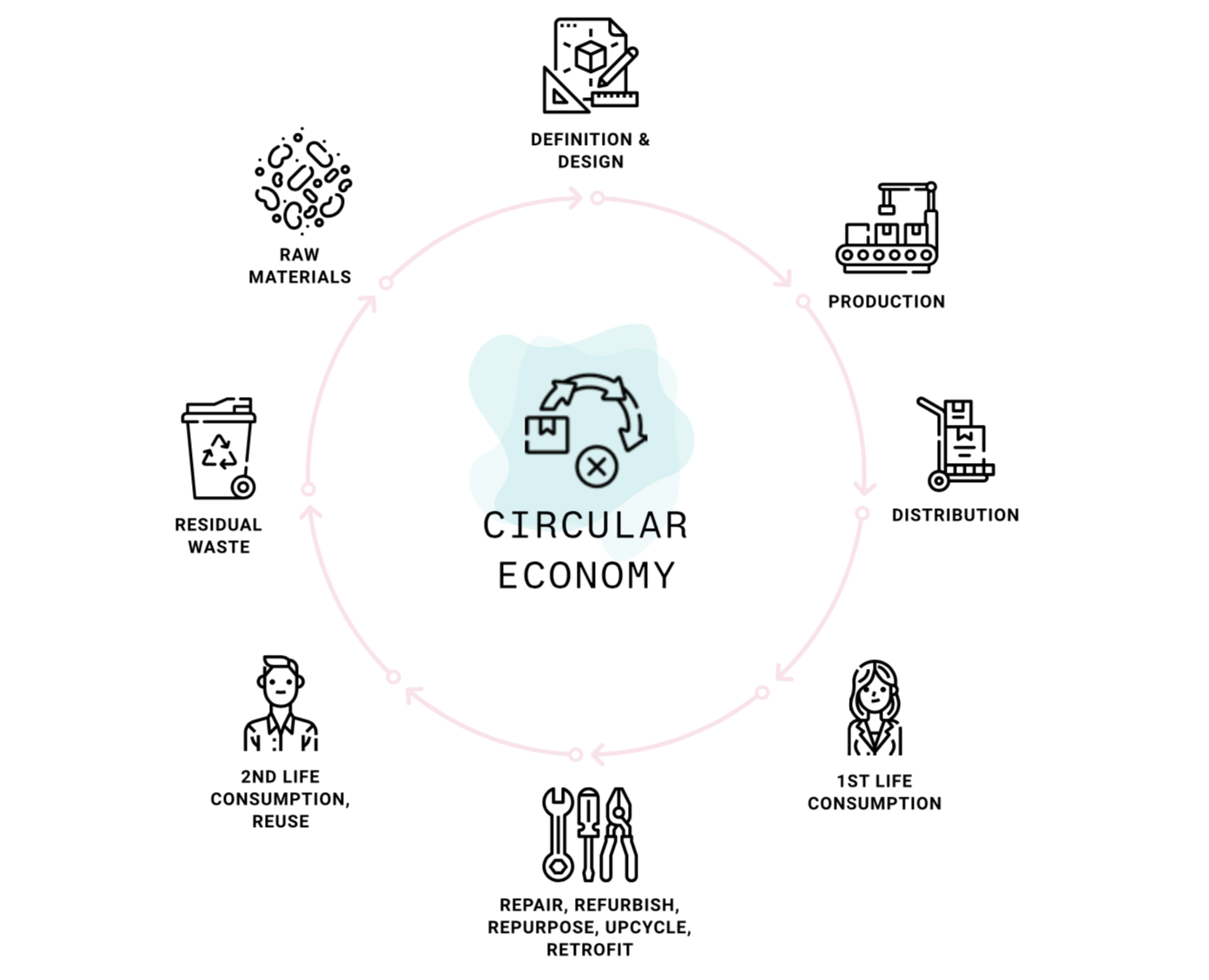

The next step beyond proposing the shortest and fastest travel options is suggesting those with the lowest carbon footprint. The automotive industry has also taken interest in the overall life cycle emissions of its products – in addition to just direct local emissions of vehicles – and is turning its production plants more sustainable and efficient. Recycling, renewable raw materials and new energy sources play a central role in this.

Where are mobility trends, structures and business models developing?

The mobility sector has been seen as relatively independent in decades past, but today it is in constant interaction with other industries and areas of business. This is particularly evident in the current shift towards electric vehicles.

The evolution towards sustainability is by no means a solo effort. It requires hardware manufacturers and operators to network and cooperate with the political and scientific spheres, and establish strong economic partnerships with component manufacturers and recycling specialists as well as with green energy suppliers, banks and insurance companies, and a retailer and service network. It also calls for business model innovation – like we are already seeing in areas like battery leasing, car subscriptions, delivery services or fast charging solutions.

Sustainable mobility requires a shift from linear economy to circular economy

The large-scale adoption of electric vehicles will also introduce new questions and challenges related to sustainability. For example, figuring out what will happen to used battery cells once they can no longer be used in the vehicle requires creative thinking to give them a second life as electricity storage, and designing a service model to adapt usage to e.g. weather conditions and to extend the service life of the battery before the valuable materials are recycled through a dedicated ecosystem partner.

The circular economy mindset has been an important driver of sustainability over the past few years, and consumer attitudes are changing as well. Campaigns advocating against planned obsolescence are also highly relevant in the mobility context, as we’ve already seen in conjunction with discussion around the life cycle of inexpensive bike share fleets and early e-scooters, as well as the right to repair movement.

The change is also propelled to a large degree by public sector support and obligations that target manufacturers. In France, for example, deliberate obsolescence has already been criminalised. Initiatives aiming to increase supply chain transparency and ensure fair practices in the smartphone industry are more than likely to land onto the mobility sector as well.

The mobility industry changes as people demand change

On the individual level, user needs will never remain constant throughout the course of life. People change jobs, move to new neighbourhoods, have children, and start new hobbies.

This has always meant switching between different modes of transportation, and will continue to do so – but as new options emerge and become more accessible, ownership is becoming less important compared to flexible access and mobility as a service.

Additionally, demand can change with new subsidies and incentives. The mobility transition is a challenge for society as a whole – switching to greener options is not a self-explanatory process if it means having to live without amenities or sacrifice freedom of choice. According to a survey by TÜV, “many city dwellers will only give up their private car when alternative mobility offers are similarly flexible, comfortable and safe” – something that remains next to impossible to offer with current infrastructure.

To solve this issue, many employers are already looking beyond traditional corporate fleets, and instead providing their workforce with mobility budgets – monthly allowances that employees can use on various means of transport to get from A to B.

Rural areas have their own set of challenges, owing to lower user counts that make it more difficult for service providers to reach critical mass to make a profit. In these areas, expanding previously existing systems has significantly more potential – for example, enabling parcel delivery vehicles to also transport passengers.

Enabling technologies play an important role as well. In order to enable new solutions, car manufacturers can build in features to simplify shared use also with strangers – from planning who gets the vehicle and when, to managing access and sharing the cost of ownership.

Mobility can become more sustainable, but also more personalised and flexible at the same time – not just for the most privileged individuals, but for as many people as possible. Technology is a great enabler – but it will only help us move towards a more sustainable future if we allow it.

Our key takeaways on sustainable mobility

- The mobility sector needs to look beyond the needs of individual users, and focus on what’s good for the big picture.

- Sustainability can take many shapes in mobility. The principles of planet-centric design and circular economy play an important role in new services and products, and data is a crucial part of making them work.

- The end goal is not to get rid of privately owned cars altogether – but rather introduce more choice and freedom with more flexible modes of transport for different situations.

Learn more about our approach to the mobility industry here.

The illustrations in this article have been designed with resources by Freepik. See all of our Digital Transformation consulting services here

Jonathan BölzLead Experience Desiger

Jonathan BölzLead Experience Desiger